November 2021

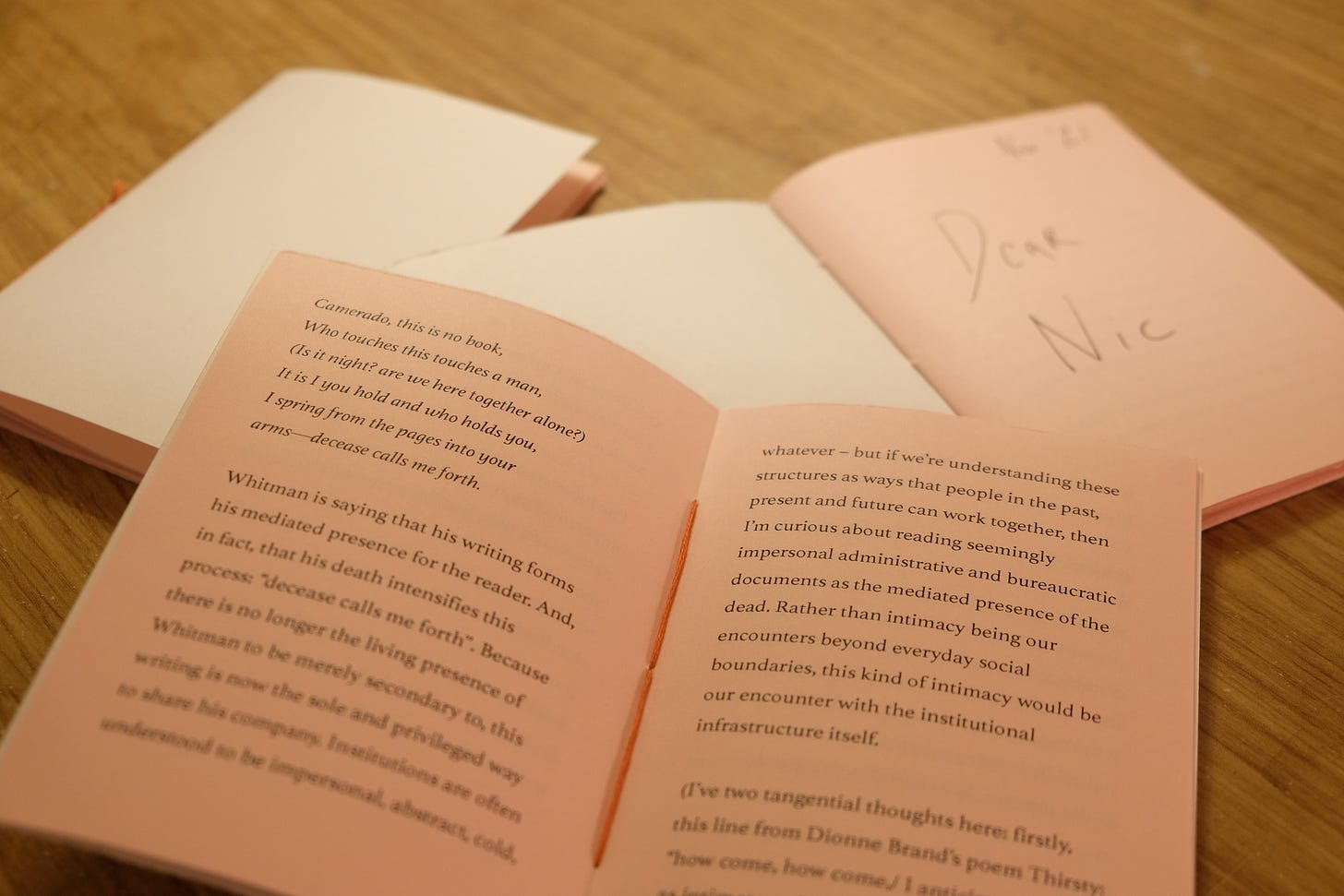

A recent letter to my supervisors, with some extra notes at the end. The photo below is of the letters, as I’ve printed and bound them this month.

Dear Nic, Robyn, Efrosini,

I’ve been writing! Writing as part of a back-and-forth with a new collaborator; for a local artist studios who are losing their space; that damned RDCom2 form1; because some friends invited me to write for something; something that doesn’t yet have a destination; and now writing this letter to you!

I’ve spoken to you before2 about one of my main anxieties about the PhD process: that artistic practice – in all of its instabilities, open-ended-ness, and its significant demand of time – can easily get crowded out when struggling to meet the university’s various demands. People go in and spend less and less time on the actual artistic practice and more and more time on the theoretical writing that surrounds (at an increasing remove from) the work, often before it’s even been made.

How far have I slid down this slope? I’ve not really been doing any ‘artistic practice’ since I last wrote, but I feel alright about the situation. Things are ticking along with a project Rohanne and I are doing with the demons; and we’re also trying to put in motion a couple of exhibition projects that’ll (*fingers crossed*) happen over the next year. I’m also ok with this simply being a time that’s thick with writing. It’s a material and practice in itself, and I’ve wanted to use the PhD to develop my skills. It’s not that I expect to make a career as a ‘writer’ after this – but it’s giving me a better sense of how I move from the beginnings of an idea (or an invitation to write) to a finished thing, and how long different kinds of writing take. I’m getting better at attending to the nuts and bolts of language itself: word choice, sentence structure, the arc and flow of each particular paragraph.

The RDCom2 asks me to account for the relationship between my writing and whatever artistic materials I’ll submit. One of the ways I describe this – and I think the relation most evident in these letters – is of using a particular strand of practice as a rhetorical context to situate some thinking. I give an introduction to the process or materials, and follows through on that description to develop some ideas. I rarely make major conclusions: it’s more about articulating persistent tensions (and perhaps pointing back to the practice as a way of navigating them). I think all this came from when I was reviewing dance performances a few years ago. I would trying to describe as precisely as I could my experience of the work – what I saw happening on stage, but also my wandering attention – and see what questions or arguments could be mined from that. I think the principle is still the same; I’m now just using my own work as the point of departure.

I think I remember Linda Stupart3 at some point saying that ‘irony’ isn’t a good register for academic writing because it relies on readers having information that isn’t explicit stated. Instead, academic writing should attempt to be unambiguous, comprehensive, and minimise presumed shared understanding. When I write, I try to go for as non-specialised language as I can. I imagine I’m introduce and explaining something to a group of friends, who have more or less familiarity with the field I’m describing. But in a conversation there’s the opportunity for back-and-forth: to ask for clarification. In writing, I’m trying to predict the potential needs of many different readers, and do all that disambiguation in advance. (I always end up packing in too much. I’m terrified of not being understood – at least in part because I don’t want to be perceived as being exclusively ‘academic’ and inconsiderate of people’s needs.)

I’ve been reading a lot of poetry over the past month. I read it aloud, and sometimes transcribe it. I often feel completely at a loss as to what the poem might be ‘saying’, but will still find myself hooked on particular lines, phrases, words. Or I’ll find my mind going somewhere else entirely. Or nothing will happen; and I’ll just notice myself having made the time for this open-ended encounter with this strange, dense material.

Most of the writing I do is pretty explicit in its purpose. In contrast, poetry (or at least, most of the poetry I’m reading) is pretty obscure. I was struck by someone on Twitter describing poetry as operating through “smooth, rude, impossible condensations.”4 It appears to be less concerned with how it invites in or situates the reader: what they might or might not know. Which is not to say that poems don’t have a frame or context, or that poet’s are unaware of what they are articulating to or withholding from their reader. It’s just that poetry (or again, the stuff I’m reading) seems willing to situate its readers with some dense and enigmatic materials.

There’s a risk of me making a binary here: between writing that is poetic, dense, affective, ambiguous, artistic; and that which is academic, measured, dry, unambiguous, uncreative, etc. There are obviously many counter-examples. But through this PhD, I am interested in thinking about how writing might be steeped in a kind of intimacy when operating in academic or administrative frame. These monthly letters – and the more ‘worked’ bits of writing I’ve produced5 – are trying to imbue themselves with an affective change, a sense of beauty, and make explicit my particular ‘motivations’ or ‘agenda’; while also satisfying the demands for academic rigour (whatever that means) and being comprehensible to a non-academic audience.

The infusion of intimacy in seemingly impersonal contexts: this is nothing particularly new. But I’m interested in another kind of intimacy in relation to writing: around absent-presence, and how that fits into this idea of institutions as trans-generational projects I’ve been working with.6 Here’s Walt Whitman’s poem So Long!7, in which he’s imagining his writing after his death:

Camerado, this is no book,

Who touches this touches a man,

(Is it night? are we here together alone?)

It is I you hold and who holds you,

I spring from the pages into your arms—decease calls me forth.

Whitman is saying that his writing forms his mediated presence for the reader. And, in fact, that his death intensifies this process: “decease calls me forth”. Because there is no longer the living presence of Whitman to be merely secondary to, this writing is now the sole and privileged way to share his company. Institutions are often understood to be impersonal, abstract, cold, whatever – but if we’re understanding these structures as ways that people in the past, present and future can work together, then I’m curious about reading seemingly impersonal administrative and bureaucratic documents as the mediated presence of the dead. Rather than intimacy being our encounters beyond everyday social boundaries, this kind of intimacy would be our encounter with the institutional infrastructure itself.

(I’ve two tangential thoughts here: firstly, this line from Dionne Brand’s poem Thirsty: “how come, how come,/ I anticipate nothing as intimate as history”8. I note her use of the term ’history’, rather than ‘the past’ – i.e. history as one of the ways the past is sedimented/materialised/mediated in the present. I’m curious about how Brand declares this mediated past as more charged with intimacy that other parts of the present. Secondly, I think there’s an ontological9 question to all this. I won’t go into it fully, but In short: it’s whether or not it makes any sense to suggest that the past ‘exists’ in a any way beyond the traces it has in the present. For example, this would mean that the idea that “dinosaurs once roamed the Earth” is less about positing that somewhere/somewhen dinosaurs are/were walking about, and more to do with the many fossils and other material traces that are in the world in the present, and the kinds of understanding and imagination that have emerged from them.10)

Following Whitman, and his investment in writing as the mediated but intimate presence of the deceased, I’m curious the form of the ‘open letter’. It’s a form of writing that is addressed to a particular person, yet is also self-consciously oriented to (and I suspect more often primarily written for the benefit of) a broader readership, potentially unknown to writer. In both cases there seems to be a something charged with intimacy, yet promiscuously available to a public beyond the writer’s awareness or individual control.

I’m thinking about these letters I’ve been sending to you. I think I’ve told you that I reproduce them online (within some contextualising notes) for a public readership (who are mostly artists or academic friends, but also a growing number of people I’ve pretty sure I’ve never met11). These letters are doing many things: they’re keeping you up to date with my work and thinking. They’re trying to make my publicly-funded research publicly accessible. They help me map out and keep track of my thoughts – and hold onto them in a way that frees me up to think about other things. They force me to clarify my ideas outside of the murky and self-confirming space of my mind; and are an opportunity to test how I want to work with paper, layout, binding, book-making. And they are generating a bank of writing, some of which might go on to be included in the written thesis. I don’t want to hit my final year, and find I need to produce 1000 words from scratch each day.

I suspect that this is all too much. The letters are overburdened with these different demands. There is a romance to Whitman’s poem that would likely be lost if it tried to also be a semi-academic text, or an organisation’s policy document. I think the ‘instrumentalisation’ of these letters means they end up losing some of their intimacy to you. While your names sit at the top of these letters, you become a kind of surrogate reader. I wonder how you feel about all this? I notice the effort I put into fabricating the letters: the choice of paper, and how it is printed, cut, folded, bound, sewn. I suspect I’m attempting to compensate for something: to make up for my divided commitments, by investing each physical letter with some material attention that is reserved for each of you.

And of course, there’s no obligation for me to send these letters in the first place – and I don’t think any of you would be upset if I stopped sending them. But I think these tensions is pretty generative. This sense of multiple-things-happening-at-once seems quite key to the PhD. But I think it’s happening here in two distinct ways. One is the sense of being motivated by various subtle and potentially contradictory desires. To put it in a psychoanalytic register: one’s actions are not simply driven by their direct relationship with others, but also about how the individual preserves their sense of self – sustaining, sublimating and satisfying desires ultimately stemming from their early development (most famously, incestuous desires that become converted and preserved as desires for those outside of the family unit, or as non-sexual expression).12 In short, that I might be driven by more things (seeking your praise, fear of failure, my need to retain control of this process, etc.) than I am able or willing to say.

The second is tied up with how particular actions might be operating within distinct (yet overlapping) economies. In the context of the PhD, I’m thinking about that in relation to the figure of the artist, especially when they’re situated in non-artistic roles, e.g. consultancy, administration, governance. How might they satisfy the institution’s idiosyncratic demands, while also serving other agendas (their own, or those of a network of peers to whom they hold a deeper allegiance)? One of the ways this can be sustained is through camp; which is, as Susan Sontag puts it, “a mode of seduction – one which employs flamboyant mannerisms susceptible of a double interpretation; gestures full of duplicity, with a witty meaning for cognoscenti and another, more impersonal, for outsiders.”13 I’m also interested in ideas of ‘smuggling’ (via Irit Rogoff) or ‘spying’ (via Felix Gonzales-Torres); Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’ ‘the undercommons’; and to dispense with the sense of duplicity or covertness, within the black feminist tradition of ‘bridging’14.

I’m meant to be producing some original knowledge about UK dance artists; but we all know that only a handful of people (including you guys) will ever read my thesis, and that this PhD probably won’t lead to a sustainable academic career. These letters are motivated by and attempting to do numerous different things – in ways that I can and can’t recognize, that I will and won’t admit to. I’m trying to make sense of and make the best of my peculiar institutional position.

Usually I include some art materials I’ve been working on in each envelope, but as I explained, these past weeks have just been full of writing. So I’ll leave this letter as it is. Perhaps, as Whitman suggests, that’s more than enough.

With touch,

Paul

An administrative form due 6 months into the PhD. I’m now 13 months in. I’ve written more about it in the letter in April.

That same letter in April.

I don’t know Stupart personally, or her work that well. They’re an artist and writer based in Birmingham. I can’t remember where I heard them saying this – it was probably somewhere on social media.

This is the tweet. After deleting my account a couple of years ago, I quietly rejoined Twitter mostly to listen into and get a better understanding of the contemporary poetry scene.

I gather together all of my ‘output’ related to the PhD here: https://www.chattingtanum.info/phd

This concept comes from Mick Wilson, and I’ve been working with it in one way or another in most of these letters. I think I spend most time with it in May’s letter.

Walt Whitman (2009) Leaves of Grass. Oxford University Press: Oxford. pp. 380-382. Available at: https://poets.org/poem/so-long.

Dionne Brand (2002) Thirsty. McClelland & Stewart: Toronto.

Ontology is a branch of philosophy that thinks about the nature of reality. For example, a classic ontological question is whether there only material things in the universe, or do non-material substances (like – ideas, concepts, thoughts, spirit) also exist?

I actually wrote one of my undergraduate dissertations (I chose to write two shorter essays rather than one long one, because I’m lazy) on the philosophy of time. It’s a relatively contemporary branch of analytic philosophy, which doesn’t particularly excite me in general, but I’d be curious about returning to some of it now that I’ve got questions I’m actually invested in (e.g. dance organisations and dead gay poets).

Hi! How are you guys doing? I am very excited that these seem to be useful or of interest to some people beyond me…. I’m so curious as to what you make of these letters, and my research more broadly. If there’s ever questions about stuff that you’d like to follow up on, or just general comments or suggestions – please do get in touch!

I’ve recently been wading through a bunch of writing that’s strongly informed by psychoanalytic theory: including Adam Phillips’ On Flirtation (1995), On Wanting to Change (2021), and Intimacies (2008) written in collaboration with Leo Bersani; and Lauren Berlant’s Desire/Love (2012). I’m not going to give a particular reference though as I’ve not yet properly gone most of it and properly digested my notes. Scandalous!

Susan Sontag, Notes on “Camp”. In (2013) Against Interpretation and other essays. Picador: New York. pp. 394-480. Also available here: https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf

In order:

- Irit Rogoff (2006) ‘Smuggling’ – An Embodied Crticality’, TRANSFORM. Available at: https://xenopraxis.net/readings/rogoff_smuggling.pdf

- Félix Gonzáles-Torres (2012 (1995)) ‘Being A Spy: Interview with Robert Storr’ in Stiles, K., Selz, P. (eds.) Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists Writings. University of California Press: Berkeley, Los Angeles, London. Available at: https://creativetime.org/programs/archive/2000/Torres/torres/storr.html

- Harney, S. and Moten, F. (2013) The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Minor Compositions: Wivenhoe / New York / Port Watson. Available at: https://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/undercommons-web.pdf

- Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (eds.) (1981) This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Watertown, Mass.: Persephone Press.

Rogoff and Gonzáles-Torres are both writing from the perspective of contemporary art. Harney and Moten are mostly talking about universities in North America. Moraga and Anzaldúa’s anthology is composed of writing from queer women of Global Majority, mostly living in North America. Rather than having any particular disciplinary or institutional focus, the writing is more engaged in everyday life and survival – although there are repeated challenges to the whiteness of feminist political organising.