January 2022

The transcript of a recent letter I sent to my supervisors. Each letter included photo prints of four of the ‘divinations’ I discuss below. For this copy of the letter, I’ve turned them into simple and low-res digital composites. You can find versions of nearly all of them on my Instagram – if you don’t have an account though and would like to see more please get in touch. As ever, I’ve included some extra notes and links at the end to support a wider audience.

Dear Robyn, Efrosini, Nic,

I want to write to you about so many things! About demons, names, and the law. About how it’s been going at Sadler’s Wells (and the complexities of speaking candidly or publicly about that). About hosting and of being a guest: what it means to make a place your home, or to reside somewhere you don’t feel particularly welcome; and how queers use clothing or affectation as a way to sustain themselves in inhospitable environments. I’m reminded of this moment in Shola von Reinhold’s fabulous novel Lote:

At night we swanned all about the town, which had become more palatial, more of a pleasure-ground than ever, amplified by Erskine-Lily’s painting of it as much as my own will to envisage it as such […] In his company, the town, already a place of alternately consoling and faintly distressing beauty, became an extension of his flat, which was in turn an extension of his attire, physical person, persona.1

But this act of projecting themselves into public space makes these figures vulnerable to racist and queerphobic attack:

When we careered about the city, the sight of us both together brought out something in passers-by which when alone was not as vehement, at least for me (people, I was coming to realise, coming to love, were terrified of me.) One day a group of English tourists, buffered into confidence by the language barrier, threw beer bottles as we passed.2

But I’m late, late, late! I didn’t get round to writing you guys a letter in October. I intended to send this in December, but it’s now the new year. Things are piling up. I want to process some of my reading and note-taking, and carve out some days – weeks! – just for the studio. I recently fantasised about taking a couple of months out of the PhD just to work through everything on my plate, but that would be ridiculous. Working through this ‘backlog’ of things is the work itself. I guess this is one of those sobering moments when the giddy potentials of the PhD – which could be about so many things! – confront the practical limits of my time and energy. This project can’t be everything. There is only so much I can bite off before I have to chew.

But anyway, isn’t this lateness the situation we’re all in? Most people I know – within or outside of institutions – are busy, stressed, stretched. Under-resources and permanently trying to stay on top of unmanageable workloads. The arts and academia seem to be full of timelines and workload allocations that in no way match up to the realities of how long things take or how they get done.

But is it just these fields, or is this a generalised post-Fordist condition of the Global North in the 21st century?3 I was astonished to read John Giorno – in his memoir Great Demon Kings – describe his job on Wall Street in the ’60, that indirectly enabled him to develop his poetry practice, and engage with the New York experimental and interdisciplinary art scenes:

In those years, Wall Street was genteel, not the cutthroat jungle that it would become […] the firm was still a gentlemen’s club of sorts. The New York Stock Exchange opened at ten in the morning and closed at three in the afternoon, and everyone took two hours for lunch. By four o’clock, I was back on the Upper East Side in bed, taking a nap.4

But he suggests that even the lucrative world of finance is not so cushy anymore. I was dating a charming guy in the autumn who works in commercial pharmaceuticals, who told me that salaries in his field have halved over the past decade as major companies now outsource the development of new drugs to smaller research labs. Still, I occasionally meet people working in different fields who have certain kinds of stabilities and structures to their jobs that shock me and fill me with envy. For better or worse, my default expectation is that the institutions I work in will not be oriented to my needs, will fail to fulfil their promises, and – if or when push comes to shove – will not have my back.

The endless conversation of ‘how to improve the dance and performance industries?’ gets revived each time another account surfaces of bullying, burn out, exploitation, discrimination and abuse. The recommendations that emerge from this discussions inevitably encourages us to take more time, put more care into each process, and invite more conversations and listening. But while they would probably help, it seems to miss the point. The broader conditions that enable these crises will persist. There is no time; there is never any time; the latest 'issue' that we need to attend to will simply be swept into the manifold of different things to which we ought to be vigilant, yet are never able to properly acknowledge or address. For things to shift – I don’t anticipate this happening any time soon – people would need to be paid more, to do a lot less.5 But the question of what should be dropped is tricky.6 Everyone has a different sense of what (or who) is dispensable, and what can not be compromised. What can each of us not bear to not do?

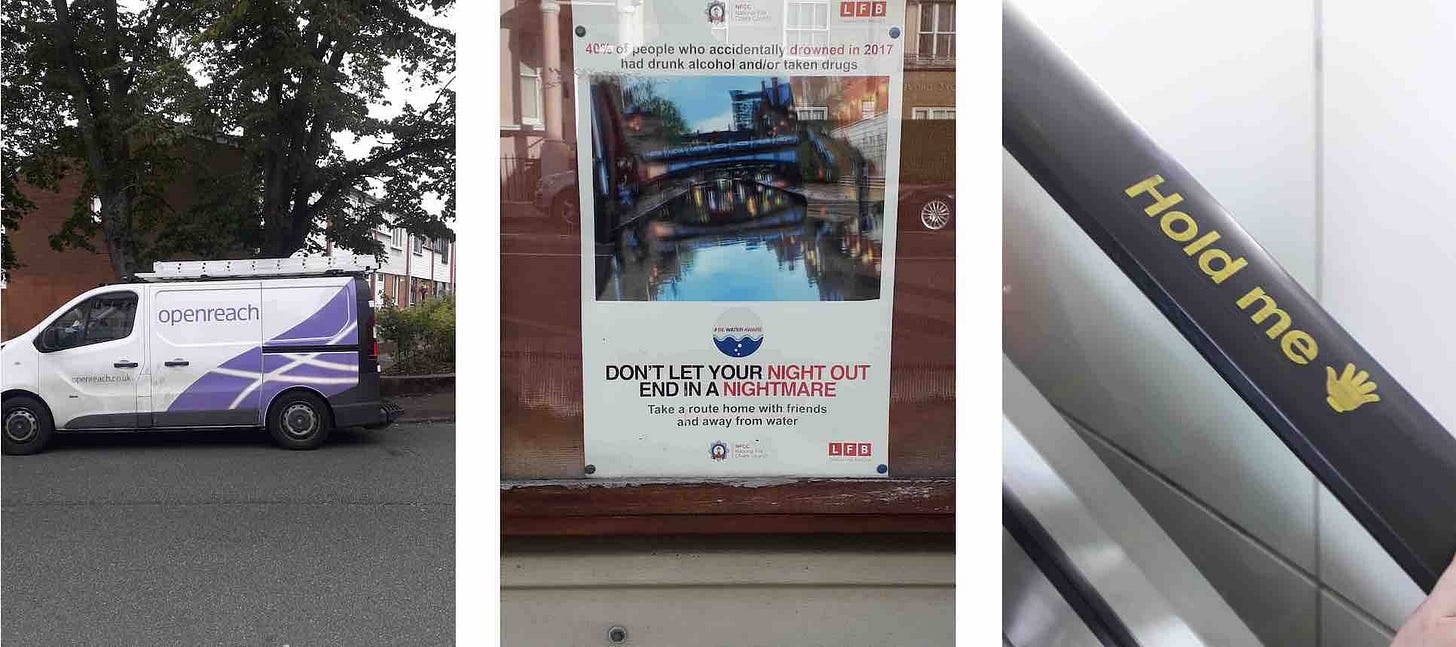

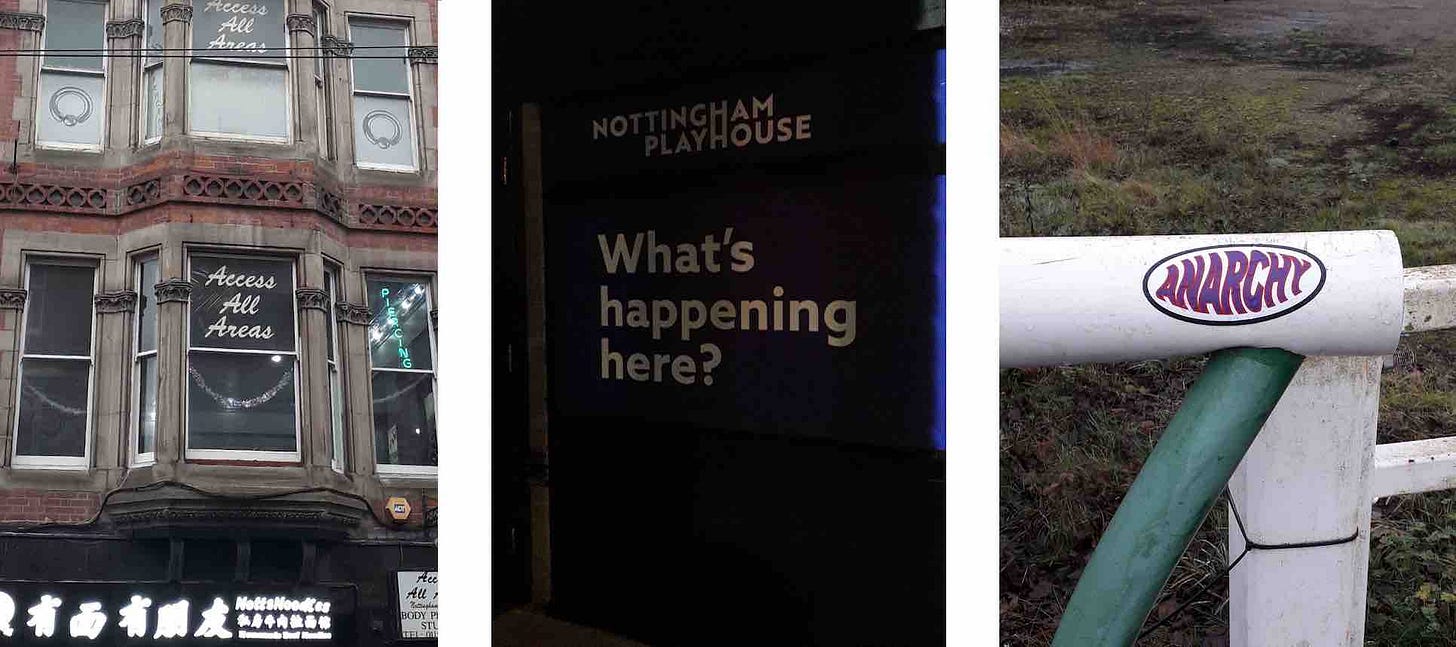

Amidst my busyness, over the past months I’ve been taking photos on my phone while walking around the city – on my way to a meeting or an event, or just taking a break while working-from-home. Combining these images in twos or threes or fours, I then post them on Instagram under the caption ‘#CityDivination’7.

All the photos – of signs, advertisements, graffiti, civic notices, discarded packaging – include some text, which strings together to read as a short poem. At first, each 'divination' was a series of things I had actually seen sequentially on the same day. But now the photos tend to hang about in my phone for a few weeks before they find some partner texts which they play off against. I tend to get interested when a particular combination begins to articulate something that veers away from (what I assume are) the texts’ original intentions. It’d be impossible to try determine the ‘success’ of any particular divination: its charm or force or capacity to ‘get away with’ itself. It comes down to a mix of humour, how the poetic meter scans, the combination of different visuals or fonts, and each reader’s sense of taste.

I find the frame of ‘city divination’ pretty useful. Some of the enduring clichés around magical practices (magic/logic, natural/human, body/mind, wild/civic, ancient/modern, authentic/artificial) get disrupted by this foregrounding of the urban context. But it's a very particular part of the city: all the photos are either taken outside or in a semi-public space (train stations, shopping centres, etc.). The series implies a figure who is outside or in-between – wandering, wondering, looking – seemingly unable enter or rest in any particular location. What do we imagine about such a person who seems to continually driven to look for meaning in these signs?

The frame of ‘divination’ encourages viewers to be a bit playful and energetic with how they read these banal texts. It’s also a useful trick to give myself permission to delve into my burgeoning relationship with poetry, without having to name it (and therefore defend the work) as such. But what would it mean to say these are ‘fake’ or ‘real’ divinations? These texts arise from my encounter with a city that is saturated with text, a busy field into which I project my imagination, preoccupations and desires. (I think of Giorno writing about his readers and audience: “They thought they were hearing my poems, but my poems were mirrors in which they were seeing themselves.”8 So even if there’s some sleight of hand in my framing, I would hesitate about discrediting them entirely. Some of my friends who practice tarot, for example, have told me that they don't see the cards as giving them access to transcendental truths, but rather as operating as tools to tease out the latent information inside of themselves when reading and interpreting the arrangements. Any attempt to definitively decide whether or not something is ‘real’ magic seems to miss the point.

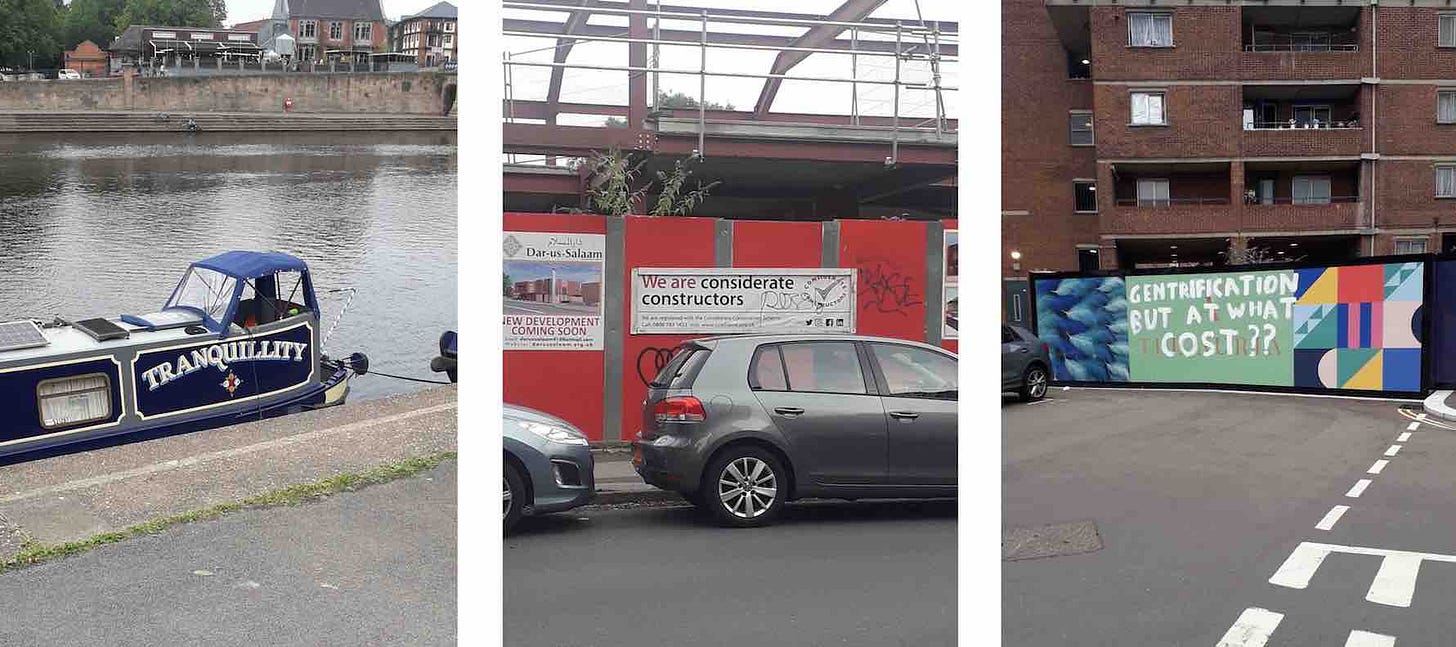

So what are my ‘imaginations, preoccupations, desires’? When I look over these ‘divinations’, I see two recurring ideas. The first is around space and power; and the second is about poetry and death. And I’m curious about how they relate.

How you feel tomorrow starts today

Private property: no turning

Tranquillity

We are considerate constructors

Gentrification but at what cost??

Stupid shit for rich people

Open to the public & trade

Perfect aesthetics and beauty

The language is steeped in the policing of space, the violence of construction and ownership9, and the challenges of belonging in a landscape that continually demands one assume the role of a paying customer. And I think the practice posits some kind of agency in the walker/reader who moves across all this. There’s the more obvious power relation between sanctioned and unsanctioned forms of writing – notices and advertisements juxtaposed with graffiti, stickers, and home-made signs. But there’s also something gently subversive in how new meanings can be produced by a reader as they walk through the city. We are not powerless when entering into an institution’s infrastructure. One’s experience isn’t determined; in moving between and across we can give rise to surprising and critical experiences, imagination, uses, life.10

This is nothing particularly new. Alongside the traditions of found poetry, I think these minor gestures fit quite neatly into the Situationist and psychogeographic legacies. The stakes are certainly lower than the work of UK practitioners like My Dads Strip Club, Richard Dedominici, The Vacuum Cleaner, etc.11 But even if there’s a repetition at play here, I think it’s useful to to keep returning to the kinds of questions these practices ask as the urban landscape continues to change. What spaces are there in the city, here and now, for opportunity, creativity, encounter, exchange, pleasure and play? In what ways do the state and capital exercise their power as we move into the ’20s? In what ways does grassroots counter-culture cohere and express itself? How thoroughly has the urban landscape of the UK become gentrified?

The idea of ‘gentrification’ has come up in a previous letters to you guys12, when I asked what it would mean to say that the institutional landscape of UK dance has become gentrified. I’m thinking of my new friend Deane McQueen, who was telling me about being at a dance center in London in the ‘80s, where practitioners used to hang out all the time, socialise and make connections, and develop projects. This feels totally unlike the London (or most arts spaces) I know. But how much is it to do with the governance of these arts spaces, as opposed to broader factors such as the increasing expense of major cities, the inability to get by on the dole or on student grants, or stagnating wages in relation to rising rents and property prices? Or the fact that there are so many more people graduating from arts degrees each year, or younger artists choosing to instead gather and circulate their work online, or artists giving up on the capital in pursuit of cheaper living around the country?

I don’t think the question of whether this or that context is gentrified needs to expect a binary ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer. As Matthilda Bernstein Sycamore writes in the opening her extraordinary book The Freezer Door, “One problem with gentrification is that it always gets worse”13. Gentrification is more layered and complex than that – and gentrifiers can find themselves priced out of neighbourhoods into which they had settled. Nottingham feels more viable to me then places like London, Manchester or Glasgow. It has a vibrant grassroots cultural life. Primary, an artist-studios-turned-NPO, one of the pillars of the city’s visual arts scene, recently got funding to purchase the old school in which it’s situated, and secure it’s future there. But recently a very comparable organisation, One Thoresby Street, heard that they are soon going to lose their space, as the neighbouring medical research center BioCity14 has bought the land and plans to extend their buildings. I was invited to write a text in response to the situation at the end of last year, in which I tried to tease out some of the contradictions and tensions of these grassroots spaces: their sense of fragility and possibility, how they simultaneously energise and demand from artistic communities, and my reservations about any desire or demand for them to endure.15

The other preoccupation that stands out for me is the relationship between writing, possibility and loss:

No parking: Funeral procession today

Rest one, at any time

Living Water

Temporary warning notice: Blue-green algal blooms

Stay

Sorry

This art will be destroyed soon

Leave a legacy

ty best boy ❤

It’s less directly addressed in the texts, but I think this second preoccupation saturates the work as a whole. The low-fi photographs express blurry glimpses of fleeting encounters. Much of what is seen evokes a sense of impermanence: not just the graffiti, but also official signage that often looks battered and fading. The divinations appear on Instagram as part of a stream of posts that users likely rapidly scroll through. Perhaps they are smirked at, or ‘liked’, but I assume that any of these individual divinations is soon to be forgotten.

City Divinations is a poetry practice that comes from moving through the city; of the temporary feelings of agency and belonging when operating outside or in-between formal institutional structures. It evokes that which eludes or exceeds institutional directives – and inherent to this extra-institutional dimension is its ephemerality and powerlessness. And I think this tension produces a potent sense of promise and erotics that runs at the core of this PhD project. There is the possibility of change, that things might be different – the possibility of possibility itself – at odds with the growing disillusionment of anything that endures (that becomes incorporated into an institution or becomes an institution itself) and as such sediments into the banal and disappointing fabric of that which exists. These City Divinations lure us with a sense of promise, despite – and through – their anticipation of a future in which they will likely disappear without a trace.16

Poetry seems to have a particular relationship with disappearance, loss, absence, the dead. In my last letter17 I wrote about Whitman’s idea of writer as a transgenerational encounter with his future readers. Poetry is not just something we comfort ourselves with in grief, but a means through which past life is held in relation to the present. I think poetry opens a space of co-presence with the dead – most overtly in the form of the epitaph18 (which we could think of as a form of monument, although perhaps of a softer or less authoritative kind than that term usually conveys).

But what of past life does poetry hold? There's a section in Ali Smith’s Artful where she moves from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55 (“Not marble nor the gilded monuments / Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme, / But you shall shine more bright in these contents / Than unswept stone besmeared with sluttish time.”), in which he claims to preserve his lover through poetry, to Edwin Morgan’s “Not Marble: A Reconstruction” (“Vulgarity / dogs marble, gildings; monuments are a mess. / […] Hordes, posterities, judges vainly cram / the space my love and I left yesterday”).19 Smith writes that “Morgan revels in the space, the not-marble, the nothing-but-air left by the lovers, into which the future can rush, fill if it likes”20 Morgan might reject the vanity and self-seriousness of Shakespeare's desire for monuments, but proposes that the gap of this love endures: “this form, made from nothing-but-air, in being so permeable, is impermeable, the lovers being gone”. It is a site of open possibility, and something curiously sealed and preserved through its disappearance. Sure, nothing endures; but nothing itself endures. I think of the question at the end of John Donne’s poem “The Computation”: "can ghosts die?”21. I note that Morgan seems to be happy to let the lovers themselves fade into anonymity with their death, while preserving the fact of their love, the activity of them having loved one another; which makes me think of Tim Dlugos's poem “G-9”, written from the AIDS ward: “When I pass, / who’ll remember, who will care / about these joys and wonders? / I’m haunted by that more / than by the faces / of the dead and dying.”22 While death forces us to relinquish the individual, maybe it allows us to better apprehend and attend to the things that exist across and in between each other, that which is beyond individuation.

I’m obsessed with the ethics of this writing-with-absence. Silent figures can be so easily made to say all sorts of things – why might I ever presume to know what the dead really think? In her poem “The Promise”, Marie Howe writes about being visited by her dead brother, who looks at her “as though he couldn’t speak, as if / there were a law against it, a membrane he couldn’t break.”23 Her poetry refuses to overstep what she can and can’t hear in his muteness. There’s an imbalance of power that isn’t easily addressed. Adam Mars-Jones (a novelist rather than a poet, but still) writes: "when you’re talking about the dead they have no dignity. You have the last word, and so I thought the only way of rectifying that balance was to remove a little of my own dignity.”24

Let me risk a definition. Rather than simply new people entering a neighbourhood – people come and go all the time – gentrification is a form of living in a place, that makes existing forms of life there no longer possible. I propose that one of the ways that we produce and sustain our lives is through our active relationship to the dead: it is a huge part of how we derive our sense of meaning, belonging and purpose.25 And so, one of the ways that gentrification can (must?) take place is through obstructing our connection to past lives. Gentrification displaces not just the living, but the absent-presence of the dead.

A repeated motif in AIDS narratives is of the institutional and domestic separation of the victim from their friends and lovers; and of their belongings being destroyed immediately after their death. I think of how activists in the 80s and 90s made the dead publicly present, both literally and in peoples imaginations: funeral processions as public marches, die-ins, David Worjnarovic's jacket (“If I die of AIDS - forget burial - just drop my body on the steps of the FDA”26), the AIDS quilt, etc. Sarah Schulman, in her book The Gentrification of the Mind27, describes how financial speculators in New York capitalised on property recently vacated through the mass death of AIDS – but argues that the gentrification of the city also required the erasure of the material, cultural, intellectual and political legacy of these lives. But this erasure doesn’t necessarily need to temporally coincide with their actual death. I read on Twitter about a former gay bar in Texas, where the ashes of many AIDS victims were scattered. There was a mural on the exterior wall, depicting the inside of the bar with many of its regular patrons. As the neighbourhood changed, different figures in the mural (presumably deemed 'offensive' or ‘explicit’) were painted over, leaving only the cat on the barstool.28 Rather than describe this as a consequence of the neighbourhood being gentrified, I’d argue that erasure of these images of the dead was necessary part of process of gentrification itself.

I’m assuming that most gentrifying acts of desecration come from ignorance, rather than being deliberate. But while it seems reasonable to ask people enter into new contexts with humility – willing to listen, learn, and ask about things they don’t understand – it also seems to ask a lot from people to attend to things that can’t directly identify or apprehend. How legible do we expect or need our memorials to be? And how long do we expect each particular memorial to endure? How robust is any slab of concrete, bit of graffiti, social media post, poem, or memory?

I'm at risk of jumping across and cherry-picking from a range of very different contexts in this letter – but I’m trying to get at something about what it means to be working across different publicly-funded institutions, each with their own complex trans-generational pasts. I’ve mentioned before by nervousness about entitlement29 – what does it take to pursue something within an organisation when it conflicts with the vision of the current administration? To go against the apparent-solidity of how this space ought to work, and how they professed it always has worked?30

I’ve been in relatively close dialogue with a particular organisation for a number of years now. Despite the relatively good-will of all involved, I can often end up feeling like an uphill battle; like my contributions are neither needed or particularly helpful; that I’m putting in a huge amount of energy and vibration into a space that remains resolutely cold and still. The new friend of mine that I mentioned earlier in this letter, Deane McQueen, is actually a co-founder of the organisation – and it’s been so strange to hear her express enthusiastic support for what I’ve been trying to do there. It’s so rare to have one’s efforts towards a different possible future of an institution so luxuriously legitimated by someone from a previous generation.31 This is very rarely the case – they are usually absent – and so I wonder: what is it to work in the company of their absence, when we are working in ways that seem to trouble or exceed an institutions orientation (in ways that, by definition, have been neatened out of said institution’s memory)? And not just those who we once knew and knew well, but also those will have never heard of? What is the possibility or limits of understanding their “joys and wonders” as our inheritance in these spaces? I turn to the opening lines of CAConrad’s poem “Glitter in My Wounds”32:

first and most important

dream our missing friends forward

burn their reflections into empty chairs

we are less bound by time than the clockmaker fears

Divining and dreaming,

Paul

Shola von Reinhold (2020) Lote. London: Jacaranda Books. p.310

Ibid. p.361

'Fordism' refers to 20th century factory production typified by Henry Ford and the Ford Motor Company – factory workers on a production line, mass production, etc. ‘Post-Fordism’ refers to the shift in the late 20th century to more networked, distributed, 'just-in-time' models of working, characterised by a breakdown in the separation of work and non-work life, greater emphasis on communication, and the valorisation of ideals of creativity, flexibility, expression, worker’s subjectivity and collaboration. Bojana Kunst (in her 2015 book Artist at Work, London: Zero Books), argues that the arts industry – and particularly the figure of the artist – exemplifies this kinds of labour, and thus the potentials for ever-increasing exploitation.

John Giorno (2020) Great Demon Kings. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p.31. I feel like there’s a risk in me citing Giorno in this way. It suggests that New York interdisciplinary practice of the ‘60s and 70s was of unique influence to current practice – and as such, that we are left in some tragic position because the economic conditions that underpinned that work being no longer the case. (Tim Lawrence, in his book Hold On to Your Dreams about Arthur Russell and the New York downtown scene, suggests that much of the counter-cultural movement in the USA relied upon the economic boom of the ‘50s and ‘60s). However there are many other legacies of artists working that time far removed from Giorno’s position, which was only available to a very narrow group of people: mostly middle class white men with degrees from prestigious universities. I’m thinking of the mostly queer female writers of colour, who were connected to the anthology This Bridge Called My Back. In her talk “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”, Audrey Lorde articulates the economic circumstances that framed her writing practices and those of her peers: “Of all the art forms, poetry is the most economical. It is the one which is the most secret, which requires the least physical labor, the least material, and the one which can be done between shifts, in the hospital pantry, on the subway, and on scraps of surplus paper. Over the last few years, writing a novel on tight finances, I came to appreciate the enormous differences in the material demands between poetry and prose. As we reclaim our literature, poetry has been the major voice of poor, working class, and Colored women. A room of one's own may be a necessity for writing prose, but so are reams of paper, a typewriter, and plenty of time.” (1984, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. California: Crossing Press). Still, it’s pretty extraordinary to read Lorde suggest that ‘a room of one’s own’ might be easier thing to acquire than paper or typewriter!

The words of the fabulous Gillie Kleiman – who has thought longer than me about labour and resources within the publicly-funded dance industry – echo in my head: “We need more artists making more decisions about more resources.” Lyndsey Winship (2020) Side hustle essential: how Covid brought dancers to their knees. The Guardian, 7 September. Available here.

There’s a bit in T. J. Clark’s The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France 1848-1851 (1973, London: Thames & Hudson) that always comes to my mind. During the 1848 French revolution, the newly established Bureau des Beaux-Arts was led by Charles Blanc. The ambition was for the State to support new programme of artwork, that boldly express the revolutionary mood through both who and what was commissioned. The scale of this plan had to be continually downsized, when all the formerly-commissioned artists – who had grown accustomed to receiving their regular commissions to sustain themselves and their families – wrote in begging for work.

Giorno, Great Demon Kings. p.381

I’m thinking of Stefano Harney and Fred Moten in All Incomplete (2021, New York: Minor Compositions), writing that “the first theft shows up as rightful ownership” (p.13). I think they’re suggesting that property is not just the seizure of the commons, but about us being forced into the logic of ownership and property. Property robs us of our freedom from ownership (or being owned).

I suspect I’m leaning on ideas discussed by Michel de Certeau (in The Practice of Everyday Life) and Jacques Ranciere (The Emancipated Spectator). I’ve read both, just not in a while. But perhaps more importantly for my research project, it seems to be fundamental to queer theory as a method. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writes: “‘Queer,’ to me, refers to a politics that values the ways in which meanings and institutions can be at loose ends with each other, crossing all kinds of boundaries rather than reinforcing them.” ‘Thinking through Queer Theory’, in (2011) The Weather in Proust. Durham and London: Duke University Press. pp.190-205.

Those artists are/were all part of a Live Art scene that was interested in public space, the overlaps of art and political action, and directly responding to and challenging the police. They’ve all worked together in the past, but I think their practices take on different inflections now. You can visit their websites here: http://www.mydadsstripclub.com/, http://www.thevacuumcleaner.co.uk/, https://dedomenici.com/.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore (2020) The Freezer Door. California: Semiotext(e). p.9

Yes, BioCity is where that charming man in pharmaceutical research works. At some point I’d like to write about ‘sleeping with the enemy’ – an important practice in artist/institutional relations.

I’m thinking of Suhail Malik here, when he speaks about contemporary art as “a promised-yet-endlessly-deferred solution to existing political and institutional realities”. Suhail Malik (2013) ‘Exit not Escape—On The Necessity of Art's Exit from Contemporary Art. Presented at Artists Space’, New York. Available here.

My letter in November ’21.

I’m currently reading Economy of the unlost by Anne Carson (1999, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press), a book about epitaphs that foregrounds the work of Simonides of Keos and Paul Celan. It's still a bit beyond my comprehension, I’ll hold back from cherry-picking any quotes here.

Ali Smith (2012) Artful. London:Penguin Books. pp.70-71

John Donne (1896) Poems of John Donne. vol I. Edited by E. K. Chambers. London: Lawrence & Bullen. pp.74-75. You can read “The Computation” here.

Tim Dlugos (2011) A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos. New York: Nightboat Books. You can read “G-9” here.

Marie Howe (1999) What The Living Do: Poems. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p.54. You can read “The Promise” here.

Adam Mars-Jones and Nicholas Wroe (2015) When you’re writing about the dead, you have the last word. The Guardian, 22 August. Available here.

I mean this both in the sense of personal friends and family who die, but more expansively too, with all the dead we surround ourselves. For example, I think this whole letter, with its excessive quoting, is the product of a kind of literary mausoleum: my own sense of self and belonging has partly been forged through the work of artists and writers who I have never met. I anticipate that this idea of ‘producing and sustaining life’ might sound a bit abstract or weird to some readers – if so, I’d recommend the work of the French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault, and his interest in the Ancient Greek notion of ascesis; in particular an interview with him in 1984, “The Ethics of the Concern for Self as a Practice of Freedom”. Rather than the idea of liberation (of an oppressed authentic, original, deep-down-true self) he’s interested in freedom: the experimentation and production of different forms of life that can be identified and legislated within civic and institutional discourses.

David Worjnarovic's was an American artist, writer and activist – you can see an iconic image of the jacket here.

Sarah Schulman (2013) The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. London: The University of California Press.

It’s hard not to think here of that quote by Mark Fischer: “emancipatory politics must always destroy the appearance of a ‘natural order’, must reveal what is presented as necessary and inevitable to be a mere contingency, just as it must make what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable.” (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?. London: Verso. p.17

There’s a whole other question here though of what it means to contradict and challenge previous generations! When do we carry on the purpose and mission of an institution, and when do we make a decision to critically depart from a founder’s wishes? For example, I was super interested to see a recent announcement by the Edwin Morgan Trust, which selects an emerging Scottish poet to grant £30k every two years. They are attempting to work around certain criteria that the prize-money is legally bound to (according to Morgan’s wishes) but that they the current board now recognize as exclusionary. I find super interesting in relation to notions of governance and stewardship. More on their Twitter here, and on their website here.